Abstract

Health messaging alone is not an adequate driver of consumer choice; thus, it is important for marketers to complement health-related information about fruits and vegetables. This research asks how marketers can change messaging to fit how people already feel and want to feel when they eat on different occasions. Consumers’ subconscious associations with foods, including fruits and vegetables, were measured using implicit association testing. Correlational analyses were used to investigate how these associations relate to food preferences on different eating occasions. Findings reveal six broad experiential association categories, grounded in emotional and sensory experiences, that are drivers of preference. Furthermore, eight key eating occasions or demand spaces are identified, most of which are associated with unique experiential association drivers. Results indicate that marketers, agencies, health professionals, government agencies and advocates interested in promoting produce consumption need to attend to the underlying experiences people are looking for when eating in different contexts, and how produce can fit those needs.

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables have been a staple part of the human diet since the dawn of agriculture around 10,000 years ago. Plant-based foods were even an important source of energy among our omnivore ancestors, the hunter- gatherers1,2. Despite this long history of reliance on fruits and vegetables as an indispensable source of energy, and the enduring variety and global abundance of these foods, people are not eating nearly enough produce3. Most consumers understand the essential health benefits of eating fruits and vegetables, yet bringing their behaviors into alignment with their understanding of what they should eat remains astonishingly difficult. Health is the core benefit and foundation of produce marketing. As an increasing number of consumer goods aim at demonstrating “natural” traits and health benefits, it is certainly prudent for the produce industry to continue educating the public on nutrition and to promote healthy eating as an essential cultural value. However, research has demonstrated that health-related messaging alone has limited impact on changing eating habits4,5 and is even prone to reactions of defensiveness6. The question that remains is, if health messaging alone is not an adequate driver of consumer choice, then what can marketers do to complement health-related information about fruits and vegetables?

Beyond serving as an instrument of good health, food (including fruits and vegetables) hold complex and important connections to cultural and social contexts, personal identity and emotional experiences7. Thus, messaging that mostly approaches fruits and vegetables as a tool for good health neglects the many other legitimate ways in which people think about and interact with food. In this article, we discuss original research showing important insights from consumers’ implicit associations with foods. We describe the subconscious, experiential drivers of food choices, including a wide range of various fruits and vegetables. This research indicates marketers, agencies, health professionals, government agencies and advocates interested in promoting produce consumption need to attend to the underlying experiences people are looking for when eating in different contexts, and how produce can fit those needs.

"Most consumers understand the essential health benefits of eating fruits and vegetables yet bringing their behaviors into alignment with their understanding of what they should eat remains astonishingly difficult."

Emotions as Drivers of Behavior

The critical role of emotions in driving eating behavior has become well-recognized in discussions around food consumption8. Studies have shown that emotional states, such as happiness or sadness, affect food choices9 (“emotional eating”) and that changing the emotional associations people hold with foods can influence their behaviors. For example, experimentally inducing positive associations with fruits through a classical conditioning procedure in which fruits are paired with positive words and images leads people to show greater preference for these fruits as a snack10.

Of course, from a practical standpoint, changing how people respond to their moods with food and how they feel about foods limits the applicability of previous research findings to marketing communications. Rather than focusing on how to get consumers to overcome emotional barriers to healthy eating, this research asks how we can change messaging to fit how people already feel and want to feel when they eat on different occasions. For example, if some people are inclined to reach for cheese puffs during a work or school break, rather than just judging this as a “bad habit,” we can instead focus on what emotional or experiential needs cheese puffs fill on that occasion and see how specific fruits and vegetables might be positioned to provide a similarly attractive alternative.

The Automaticity of Eating

Health-related messaging relies on “rational” appeals – things people consciously think they should do or even want to do. However, on any given occasion, whether people are reaching for packaged food or produce, they are still looking to achieve an experience from that choice. That experience tends to be emotional, and thus driven by subconscious, automatic processes that can override conscious values and intentions to eat healthy foods. On the other hand, things people think they should want or even know they do want from a common-sense perspective can paradoxically have negative emotional associations that stand in the way of choice. For example, women rationally want lingerie that is comfortable, but descriptions of “comfort” can actually have a negative impact on choice for a product, while descriptions that highlight attributes such as “lace” are more likely to drive preference. While “comfort” in this category might evoke negative emotional associations of frumpiness (e.g., “granny panties”), “lace” speaks emotionally to women’s desire to feel attractive and sexy, even while wanting comfort.

Physical and social contexts, such as whether someone is alone or with friends, at home or work, play an important role as cues in determining what products and product associations are evoked in consumers’ minds and the choices they make11. For example, a study of shopping behavior found that the presence of parents while shopping decreases impulse purchasing, whereas the presence of friends tends to have the opposite effect, presumably because parents activate a consumer’s sense of responsibility while friends stimulate spontaneity17. These automatic or habitual responses to contextual cues are difficult to override with goals, such as wanting to be healthy12.

The mind forms associations automatically, such as between “watching TV” and “relaxation,” and the automatic activation of these associations in a given context, such as when a person gets home from work, can lead directly to behavior with minimal conscious control13. When these associations are evoked, they are used as information by our non-conscious minds to drive our behaviors in an automatic and efficient way. Unfortunately, this process can sometimes make us too efficient, in the sense that our emotions and other subconscious associations can override behaviors that our conscious minds know to be better decisions. We explicitly know that it would be healthier to get some exercise after work, but the emotions evoked by seeing one’s TV overrule the rational mind. In defense of human nature, our mental resources are limited, and we must rely on associative, non-conscious processes to get through the countless small and large decisions we make at any given moment in the day. Rather than fighting against these processes, it is important to understand how we can leverage these types of associations and emotional motivations to nudge behaviors.

“Whether people are reaching for packaged food or produce, they are still looking to achieve an experience from that choice.”

Emotional states motivate consumers to turn to foods they believe will bring about a change in how they feel, whether that is relief from anxiety, a state of happiness when one is sad, or amusement to alleviate a feeling of boredom. These emotions are also closely tied to the sensory experience of taste. In fact, taste is so intertwined with emotion that this tie is reflected in language, such as when we use the word “bittersweet” to refer to a feeling of nostalgia14. Given the strong role of emotional and sensory experience in food choices and that these factors operate in an automatic and sub-conscious fashion, it is important to study these processes at an implicit, nonconscious level. Consumers might want to be healthy eaters, but subconscious associations they hold with the (sensory-emotional) experience of consuming different foods drive their preferences. As a result, when asked in a focus group or on a questionnaire how they feel about different foods, they might express positive views of fruits and vegetables because they have sincere desires and intentions to eat healthy foods. However, when making in-the-moment eating decisions, their behaviors may tell a different story about the associations they hold with foods and which associations drive their actual choices.

In this study, we investigated the specific experiential preference drivers of consumers for different foods, including a wide variety of fruits and vegetables. These preference drivers were studied in the context of different eating occasions, as physical and social contexts (time of day, who people are with) are important determinants of consumer behavior. Because consumers do not have a keen awareness of the experiential needs they are looking to fulfill with different foods in different contexts, our analyses directly study behavioral drivers at a subconscious level. We also used a choice trade-off exercise to obtain a more accurate measure of behavioral preferences than traditional survey self-report measures.

Methodology

A survey was completed by 7,061 adults (58% female) who participate in making food decisions for their households. Respondents were drawn from the U.S. general population, including both low and high produce consumption regions. Over a third (39%) of respondents lived in households with children under 18.

The Sentient Prime® implicit association testing platform was used in an online survey environment to test consumers’ associations of 56 food items from three categories (fruits, vegetables, non-produce) with 47 attributes (see Appendix for full lists of foods and attributes tested). The Sentient Prime® platform quantified each consumer’s associations in an exercise in which they were primed with food items, followed by a sorting task that measured associations between the food item prime and the attribute.

In addition, a choice-based conjoint (CBC) exercise was conducted using the Sawtooth Software platform to assess preferences for the 56 food items on different occasions (e.g., breakfast, afternoon snack), physical settings (e.g., at home, work/school), social setting (e.g., by oneself, with friends) and mode of consumption (on its own, as an ingredient). This part of the study was intended to both dimensionalize eating occasions or demand landscapes and identify consumer food preferences on these different occasions.

At the end of the survey, consumers were asked in a traditional, explicit survey format to rate the importance of different food qualities, such as “fresh” and “organic” when choosing foods to eat. They were also asked to indicate which of 13 attributes (e.g., “healthy,” “nutritious,” “convenient,” “cool”) they associate with fruits and vegetables in various forms (fresh, canned, frozen).

Results

Responses to the explicit questions, which are consistent across a broad range of demographic groups in the U.S., show that consumers are most likely to view fresh fruits and vegetables as “healthy” and “nutritious” (75-80% of respondents selected these attributes for fresh fruits and fresh vegetables), whereas only a minority of consumers (35-46%) see them as “modern” or “cool.” These results confirm that the health benefits of fruits and vegetables are well-ingrained in consumers’ minds. At the same time, fruits and vegetables are not viewed in a way that suggests they have popular appeal from a more intangible, emotional standpoint.

Interestingly, when it comes to choosing foods to eat, people place the greatest priority on a defining quality of fruits and vegetables – “fresh” (85% rated as “very” or “extremely” important) – above qualities associated with processed foods, such as “frozen” (28% rated as “very” or “extremely” important). Thus, from a rational perspective, consumers indicate many upsides to choosing fruits and vegetables, including healthfulness and freshness. However, our core analyses using subconscious and behavioral measures tell a more complex story.

“Taste is so intertwined with emotion that this tie is reflected in language, such as when we use the word “bittersweet” to refer to a feeling of nostalgia.”

Demand Landscapes

The first discriminating factor we uncovered was whether a food item is considered a meal or a snack. Processed foods are significantly more closely associated with snack categories, while produce is more likely to be associated with meals. These associations indicate that fruits and vegetables are often excluded from consumers’ consideration sets for a major category of food consumption – snacking. This finding is also consistent with PMA’s other research showing that consumers have very circumscribed perceptions of when fruits and vegetables should be consumed. For example, fruits are relegated to food occasions that consist of a single item (e.g., breakfast, snack) and don’t involve much cooking/blending of ingredients (e.g., lunch at work/school). On the other hand, vegetables are seen as one component of a multi-ingredient dish or a side dish rather than the star of a meal itself. Vegetables are also less likely to be considered when there is little time to prepare a meal. To motivate greater produce consumption, consumers therefore need to broaden their concepts of when fruits and vegetables can meet their needs.

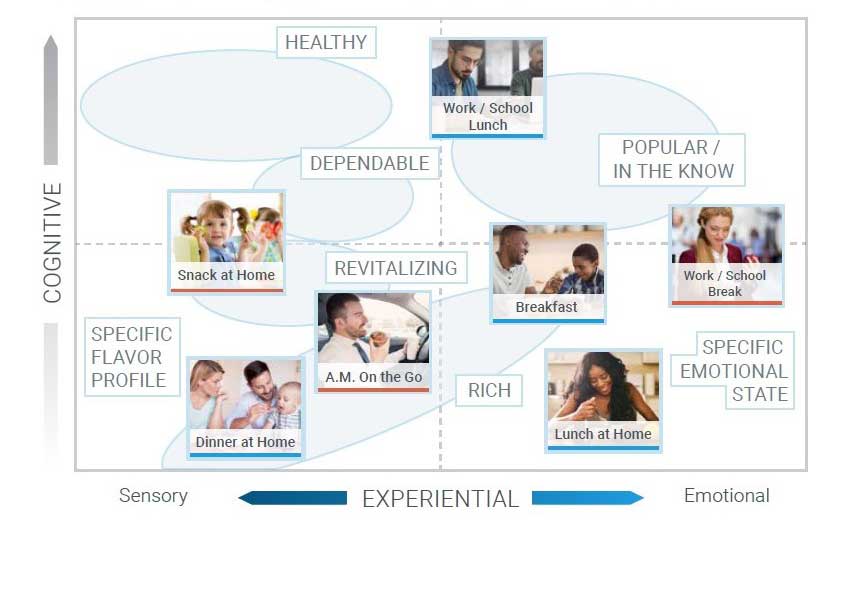

The meal and snack categories were further divided into 8 demand spaces (see Figure 1) that reflect different eating settings and times of day. These demand spaces serve as the contextual framework for the subsequent analyses.

Figure 1.

The resulting 8 Demand Spaces can be said to reflect

various MEAL TIMES or SNACK SETTING

Food Association Drivers of Preference

Social expectation and hunger show the highest correlations with preference for food items across the demand space. Thus, features of the social context – likely cultural norms driving what people typically eat – and the fundamental state of hunger, are foundational drivers for food choices. This finding suggests that peoples’ food choices are the result of relatively unreflective, contextually and culturally, as well as biologically, determined automatic processes.

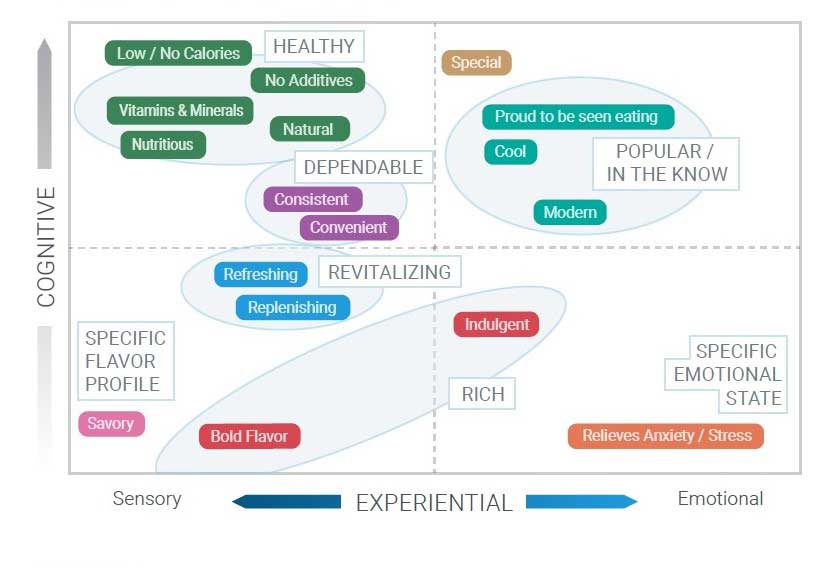

In addition to these associations, correlations between implicit associations of foods and drivers of preference in the demand spaces reveals six broad experiential association categories that are drivers of preference

(see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Taxonomy of Food Associations

These categories are based on clusters of associations that share similar characteristics in terms of where they fall on a spectrum of experiential and cognitive. The experiential dimension encompasses sensory experiences of foods, including taste and signals of satiation of thirst/hunger and emotional associations. The emotional associations can be basic (e.g., happiness, sadness, relief, anxiety, etc.) or complex and reflect a consciousness of others’ judgments (e.g., “self-conscious” emotions such as pride or shame). The cognitive dimension refers to knowledge of qualities that are functional (e.g., convenience) and intrinsic to foods (e.g., nutritional profile) or related to an awareness of how others perceive the food (i.e., socially constructed and learned perceptions):

- Specific Emotional State – foods associated with a specific emotional need. Reacting to feelings of anxiety/stress is the defining driver in this category. This association suggests the use of food to feel relief and calm.

- Richness – wanting a flavor and food experience that is indulgent and bold. Indulgence and bold flavors define this category that straddles both sensory and emotional experiences. Richness could be related to a range of emotional drivers, including the seeking of a state of happiness, elevation (feeling uplifted) or even bliss.

- Popular/In-the-Know – addresses an emotional need to feel acceptance and pride in oneself. This category embodies the idea that eating is a social activity and the foods we eat are ultimately culturally driven. Associations with cool, modern and proud to be seen eating are key to this category, and all are anchored in perceptions of foods that are socially shared or experienced.

- Specific Flavor Profile – refers to the seeking of a specific taste experience. Savory emerged as a key association in this category. Meeting the desire for a specific flavor could bring about an emotional state of contentment, satisfaction or relief from feeling a lack of physiological equilibrium. For instance, savory tastes signal that a food is rich in protein, 15 and the positive emotions we feel in response to this flavor profile serve as powerful motivators to meet biological needs.

- Revitalizing – a close bridge to more rational perceptions of the need for something to replenish one’s energy, but still rooted in a more sensory desire for feeling that something is refreshing. In contrast with “rehydration,” the associations in this category suggest the seeking of an emotional state of happiness, satisfaction or contentment.

- Dependable – reflects the seeking of something that is familiar and easy. Consistent and convenient define this category. These associations could indicate the desire to attain or maintain an emotional state of calm.

An additional association category that emerged– Healthy – is the only category of associations that is negatively related to preference. This category is defined by rational assessment of nutritional features of a food and the degree to which it is natural vs. processed. This category is positioned on the far end of the cognitive spectrum because the associations are so highly based on information about a food’s nutritional qualities. Healthy is also positioned at the far end of the “sensory” side of the experiential spectrum as an indication of rational knowledge that these food features are linked to physiological satiation. The negative association of this category with food preference reinforces previous research findings indicating that health messaging alone is not an effective driver of preference.

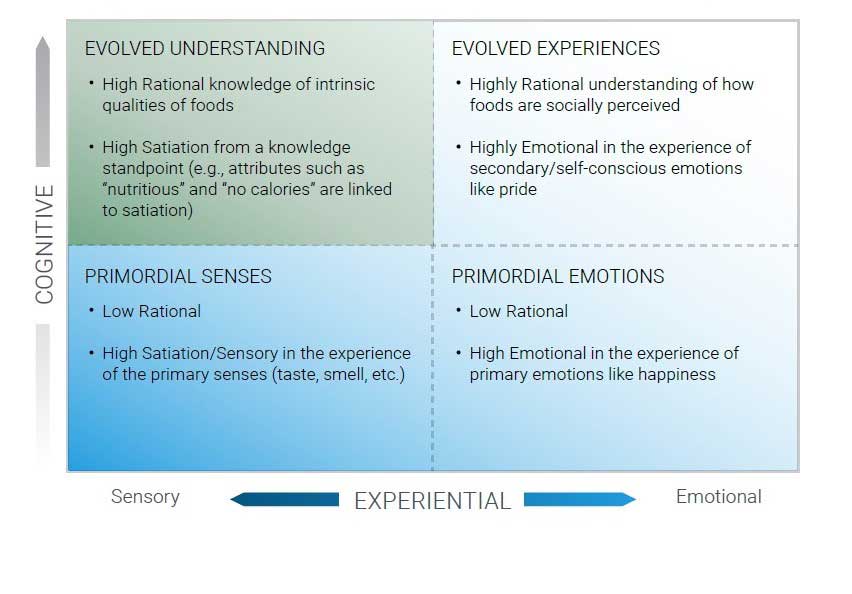

The food association categories can be further summarized by the characteristics they share based on their positioning on the two-dimensional, experiential-cognitive space (see Figure 3). While categories in the Primordial Senses and Primordial Emotions quadrants refer to more basic innate human processes, those in the Evolved Understanding and Evolved Experiences quadrants refer to responses that are acquired or learned from exposure to information and social experiences.

Figure 3

Four Quadrants of The Food Associations Taxonomy

Demand Space Drivers of Preference

Seven Demand Spaces also map to the different experiential associations (see Figure 4 for experiential category associations and Table 1 for associations with specific attributes within the categories).

Figure 4

Experiential / Cognitive Profile of Demand Spaces

- Breakfast – Food preferences in the Breakfast demand space are driven by associations in the Rich and Popular/In-the-Know category. Food items that elicit perceptions of modernity and indulgence (e.g., Smoothies) have an advantage. On the other hand, health associations (low/no calories in particular) are negatively related to preference. This profile of breakfast suggests that consumers need to be enticed to something that wakes their senses in a pleasurable way (e.g., bold flavor), gives them a needed blood sugar boost and starts their day with a sense of belonging and being part of modern life (through a food that is seen as popular).

- A.M. on the Go – The A.M. on the Go demand space is characterized by preferences for foods seen as Revitalizing and Rich. The need to feel energized, awakened and to pull oneself through a hectic morning routine likely attracts consumers to foods they perceive to be refreshing and that feel like a small indulgence to provide a momentary break or treat during the morning rush. In fact, “need a break” and “need a treat” are need state associations that predict preferences in this space. On the other hand, as with breakfast, Health associations (especially Low/No Calories) are negatively related to preference.

- Lunch at Home – Food preferences for Lunch at Home are strongly characterized by associations with Specific Emotional States, namely Relieving Stress/Anxiety (e.g., foods with many small pieces), perhaps due to the relative privacy of this meal setting which allows for a reflection on one’s emotional state. There is also self-expression evident in food choices in this demand space, with a bias toward associations with Popular/ In-the-Know, especially Modern.

- Work/School Lunch – The Work/School Lunch demand space is driven by food associations that fall into the Dependable and Popular/In-the- Know categories. Given the relatively public space this eating occasion occupies (in the presence of colleagues, peers), consumers approach this meal with a consciousness of the “coolness” of the food they are eating and the need to feel proud about what they are consuming. Consumers also want foods that are convenient and consistent, likely due to the limited time people have to make food selections and eat while at work/school.

- Work/School Break – Food preferences in the Work/School Break demand space are characterized by an inverse relation with Healthy, but are not strongly associated with any particular experiential categories tested in this study. Perhaps experiential preferences vary depending on the specific mood corresponding with a given break (negative emotional state, catching up with a colleague, indulgence in a positive distraction, etc.).

- Snack at Home – Snacking at home is typified by foods that are Revitalizing and more specifically satisfy the need to “replenish” physical and emotional energy.

- Dinner at Home – The primary driver for dinner at home is a Specific Flavor Profile – Savory – indicating a strong expectation for a meal with satisfying tastes from protein-rich foods.

Table 1

Discussion

The results of this study clearly demonstrate that, across demand spaces, consumers are motivated by a range of experiential associations that speak to their emotions and taste buds. It is notable that these results were found across demographic groups and that the implicit differences between groups were not vastly different. While certain demographic groups might be more likely to eat healthy foods based on their lifestyle and social surroundings, they are nonetheless still looking for certain experiences from eating. This study also included a range of both produce and non-produce items and indicated that regardless of the food type, people are motivated by experiential associations.

Health associations on their own work against food preferences. Perhaps at an implicit level, people have learned to associate “healthy” with qualities that are the opposite of what they desire from a more experiential perspective. For example, children are often denied “treats” such as cookies until they have eaten something “healthy” or are simply told “No, that’s not healthy.” Adults often forgo dessert with the intention that they want to be “healthy.” These findings are consistent with experimental research that showed people consumed more vegetable dishes when they were labeled with indulgent descriptions because they evoked the experience of eating those kinds of food16.

Our results do not mean that healthfulness should be avoided. Rather, it is a powerful foundation that should be built upon. Healthful claims should not be relied on solely to drive consumption without being framed with the experiential qualities of the foods that people are seeking. In fact, if consumers are aware that a food is healthy, as well as enticing and satisfying from an experiential standpoint, this information could be a strong motivator for eating healthy foods. By appealing to the experiences people are seeking at an implicit level, produce marketing can deliver on the broader needs of consumers and hold its own as a viable, healthy and enjoyable food choice.

References

- Gibbons, Ann. The Evolution of Diet. National Geographic Magazine, September 2014. Obtained from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/ foodfeatures/evolution-of-diet/ LINK NO LONGER ACTIVE

- Rupp, Rebecca. Prehistoric Dining: The Real Paleo Diet. National Geographic Magazine, April 2014. Obtained from: https://www.nationalgeographic. com/people-and-culture/food/the-plate/2014/04/22/prehistoric- dining-the-real-paleo-diet/

LINK NO LONGER ACTIVE - Lee-Kwan, S.H., Moore, L.V., Blanck, H.M., Harris, D.M., Galuska D. Disparities in State-Specific Adult Fruit and Vegetable Consumption — United States, 2015. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, November 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6645a1.htm?s_ cid=mm6645a1_w

- Sharps, M., & Robinson, E. (2016). Encouraging children to eat more fruit and vegetables: Health vs. descriptive social norm-based messages. Appetite, 100, 18–25.

- Maimaran M., Fishbach, A. (2014). If It’s useful and you know it, do you eat? Preschoolers refrain from instrumental food. Journal of Consumer Research, 41, 642–655.

- Liberman, A., Chaiken, S. (1992). Defensive processing of personally relevant health messages. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 669-679.

- Nordström K, Coff C, Jönsson H, Nordenfelt L, Görman U. (2013) Food and health: individual, cultural, or scientific matters? Genes & Nutrition, 8, 357-363.

- Köster, E. P., & Mojet, J. (2015). From mood to food and from food to mood: A psychological perspective on the measurement of food-related emotions in consumer research. Food Research International, 76, 180-191.

- Garg, N., Wansink, B., & Inman, J. J. (2007). The influence of incidental affect on consumers’ food intake. Journal of Marketing, 71, 194-206.

- Walsh, E. M., & Kiviniemi, M. T. (2014). Changing how I feel about the food: experimentally manipulated affective associations with fruits change fruit choice behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 322-331.

- Higgins ET. Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: The Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 133–168.

- Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Labrecque, J. S., & Lally, P. (2012). How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 492-498.

- Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American Psychologist, 54, 462-479.

- Samson, K., Dye, M., & Sherman, S. J. (2014, January). Is chocolate as bittersweet as nostalgia? Cross-modal priming effects for taste and emotion. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (Vol. 36, No. 36).

- Rolls, Edmund T. (2015). Psychology of Taste and Smell. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, Vol 24. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 26–31, James D. Wright (editor-in-chief ).

- Turnwald BP, Boles DZ, Crum AJ. Association Between Indulgent Descriptions and Vegetable Consumption: Twisted Carrots and Dynamite Beets. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1216–1218.

- Luo, X. (2005). How does shopping with others influence impulsive purchasing? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15, 288-294.

Appendix

Food Items Tested

Fruits

- 100% Fruit Juice such as orange, apple, grape or cranberry juice

- Apples

- Bananas

- Berries such as blueberries, strawberries, raspberries

- Cherries

- Oranges

- Watermelon

- Grapes – red, green or black

- Peaches

- Pineapple

- Pears

- Dried Fruit, such as raisins, figs or dates

- Fruit salad

- Grapefruit

- Mandarin/Clementines

- Pomegranates

Vegetables

- Kale/Spinach

- Lettuce

- Baked, Mashed Potatoes

- French Fried Potatoes

- Pre-made salad in a plastic container

- Fresh salad that you make at home

- Mushrooms

- Regular/Cherry Tomatoes

- Carrots

- Cucumbers

- Corn – either on or off the cob

- Green Beans

- Peppers

- Beans such as Lima, Kidney, or Black

- Broccoli

- Avocados

- Asparagus

- Sunflower seeds/nuts

- Greens, such as Collard greens, bok choy, swiss chard

- Beets

- Squash, such as zucchini, butternut and acorn squash

Non-Produce

- Sandwich

- Pizza

- Pretzels

- Trail mix/Dried Fruit & Nuts

- Iced Coffee – freshly made or pre-packaged in a bottle

- Candy such as Reese’s Peanut Butter Cub, M&Ms, or Skittles

- Cookies

- Rice/Pasta

- Crackers

- Breads/Pastries/Donuts

- Chips, such as potato or tortilla chips

- Cold Cereal such as Cheerios, Frosted Flakes or Honey Bunches of Oats

- Granola/Fruit Bars

- Yogurt

- Beef Jerky

- Protein Drinks/Protein Bars

- Fruit/Vegetable Smoothie

- Hot Coffee/Tea

- Regular / Diet Soda

Attributes Tested

- Fresh

- Great Tasting

- Savory

- Sweet

- Indulgent

- Crisp/crunchy

- Smooth

- Juicy

- Salty

- Refreshing

- Sour

- Single Serve

- Bite Size

- No/Little Prep Required

- Messy

- Consistent

- Spoils Easily

- Affordable

- Special

- High in Fiber

- Low/No Calorie

- Contains Vitamins/Minerals

- Bold Flavor

- Natural

- Healthy

- Fun

- Cool

- Modern

- Nutritious

- Proud to be Seen Eating

- Worth Paying More For

- Convenient

- Boring

- Good in Hot Weather

- Good in Cold Weather

- No additives/preservative

- Available

- Contains Added Sugar

- Seasonal

- Available

- Eat when I’m hungry

- Eat when I’m low on energy

- Eat when I’m anxious or stressed

- Eat when I’m bored

- Eat as a social expectation

- Eat when I need a treat

- Eat when I need to replenish